I also did an interview about this piece with Jess Conway for SCO News which hopefully offers some background:

When did you decide you wanted to become a composer?

I was quite young, and I wanted to aspire to something that would top my older brother and sister, who are both instrumentalists. Composer seemed to fit the bill: what little brother wouldn't want to write the tune their siblings had to dance to? As well as an extremely supportive family, I was fortunate to have a piano teacher (Rob Foxcroft) who encouraged me to improvise as much as possible, as well as introducing me to a wide range of new music – I had quite narrow tastes as a teenager, pretty much Schubert and Queen; Old Blind Dogs too when I joined a ceilidh band. I remember learning some movements of Messiaen's Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus and them being the first pieces of (relatively) contemporary music I actually enjoyed. But once I opened my ears, what a world there was to explore – and the best thing being I could create it as I discovered it! So, just as I was discovering I didn't really have the patience to do the slow methodical focused practice required to be a violinist, I found I did have the patience to do the slow not-always-methodical work of composing music.

Did you play an instrument first? Does that help you when you are composing?

I use anything I can get my hands on to help when I'm composing – violin, piano, singing, computer synthesis, persuadable instrumentalists and singers... Getting the actual sound right is so important, and my ears are a much better judge than my eyes, I find, or at least a different judge. Pitch matters; how music moves in time matters. But also the years spent playing in orchestras and a sense of the physicality of what I'm writing are invaluable.

Do you ever miss being the one on stage?

So much. I'm an attention-seeker as much as a control-freak.

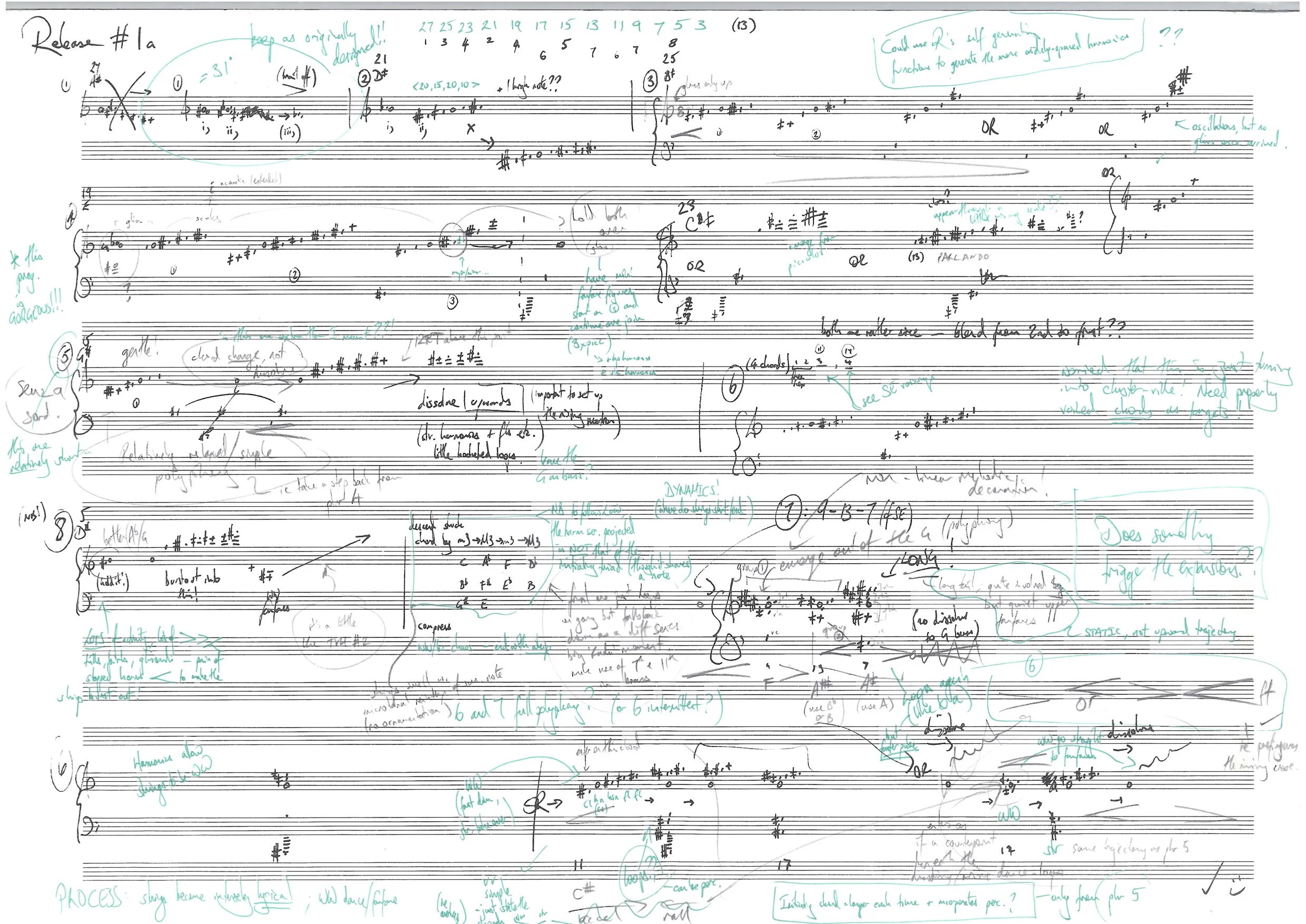

What does your first draft of a score look like? Fully formed/sketches/different colours/detailed/visual/wordy?

It depends on the piece. Sometimes there's a specific moment of music that arrives almost fully-formed and I can write that out and see where it leads; other times I have a sense of where I'm going but I need to use a lot of words and try a lot of wrong directions before I get there. Each movement for this Piano Concerto has been quite a different experience to write. The one constant is a stack of fineliners of as many different shades as possible which I periodically replenish. When working on a piece, I have to be creator, critic and coach, and it helps to have different 'voices' in different colours – plus it makes me happy.

Do you always use a specific stimulus when composing (like the Niall Campbell poem ‘And This Was How It Started’ which inspired your new Piano Concerto which we premiere in October)?

I find it helps to have some fixed point around which ideas can crystallise. Last year my 'sources' were mainly visual – Goya and Edmund de Waal – but I think all the pieces I've written for the SCO have had a literary connection – Borges for storm, rose, tiger; Shakespeare for Six Speechless Songs; and now Niall Campbell for the Piano Concerto. I read Campbell's book Moontide in 2014 while I was making the first sketches for what became this concerto and I was utterly seduced. The myth of a world created through song is an old one I've long been attracted to, and the everyday magic of Campbell's pub singer seemed to me just what I wanted from my soloist – there's virtuosity there, but it's not an antagonistic situation, more of a celebration, life-affirming.

Did you become a dad a couple of years ago? Has this changed your perspectives on composition, or has it had any other effect on how you compose?

It changes your perspective on pretty much everything! Practically, it means I need to be much more efficient. That's definitely still a work in progress. I also seem to have shifted from writing very late at night to writing very early in the morning.

As a Glasgow-born Scot, do you feel an affinity with all things Scottish? Haggis, Burns’ poetry, Scottish music…?

Hah! You know, I won the 'Scottish Songwriter in Schools' competition with a song about haggis I wrote in primary school, so maybe... But actually it's really complicated: yes I play the pipes and I sorely miss my ceilidh-playing days, but I got into these as a classically trained 'outsider'. And one of the wonderful things about so much that we consider quintessentially Scottish is that it's really international rather than provincial in nature – bagpipes occur in a great many cultures; our fiddle playing embraces traditions from the whole Celtic diaspora, not to mention Scandinavia; Burns was an internationalist (think 'The Slave's Lament'); the line singing of the Outer Hebrides (which I simply adore) became transformed in the Americas. . .

If you had to pick a composer from the 18th or 19th centuries to work or study with now, who would it be?

It depends on what we'd be doing, I can imagine many of them would be difficult to work with! They say you shouldn't meet your heroes, but still I'd have to go with Schubert. Or Berlioz – his orchestral imagination is extraordinary and I'd love to bring him back to the 21st century and see what he'd do with our resources. He described an orchestra of 120 violins, 40 violas, 45 cellos, 35 double bass, and 4 octobasses alongside a corresponding quantity of wind and brass – imagine what would happen if he got his hand on a computer and ambisonic speaker array!